KAII HIGASHIYAMA: A HAZY SHADE OF EGO

|

| Sound of Waves (1975) |

Presenting 154 important works and sketches, the exhibition ranges from early works, like the luminous color on silk study “Autumn in the Mountainous Country” (1928), through the emergence of his trademark style, to later forays into monochrome painting, and works from his final decade.

While his earliest works, replete with elements of Western realism, are a joy to behold, they have the slightly anemic quality common to Nihonga works that veer too close to Western art without actually crossing the border into the solidity of oils and canvas. “Mt. Yakedake in Early Winter” (1931), for example, is ambitious in its composition, impressive in its precision and artistic technique, and soothing in its tonality, but fails to convey the visceral impact of mountain scenery.

|

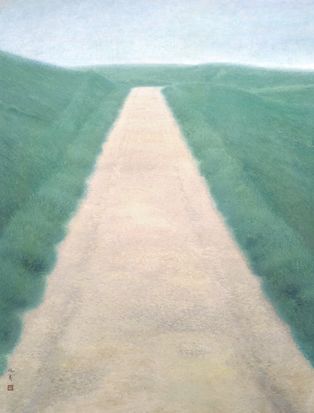

| Road (1950) |

According to one of the exhibition curators, Masaaki Ozaki, this work also resonated deeply with post-war Japan.

“The simple and straightforward, refreshing and bright atmosphere is precisely Higashiyama’s sentiment at the time,” Ozaki writes in the exhibition catalogue. “Perhaps it also concurs with the social conditions of the time, having struggled through the postwar chaos and become able to spot the light.”

Such subtly resonant paintings – as well as ambitious large scale works, like the astounding “Sound of Waves” (1975), a 36-meter long ocean panorama painted on 12 fusuma panels for the Toshodaiji temple in Nara that is the visual highlight of the exhibition – have enshrined Higashiyama’s reputation for spirituality, a quality the exhibition presentation and catalogue constantly din into us.

But, without actually explaining why his art is ‘spiritual,’ describing an artist as having “great spiritual depth” is merely lazy curating that aims to create a positive, pseudo-religious and uncritical attitude. To validly use a term like this in art criticism, it is vital to have a definition.

In addition to its religious uses, spirituality is also a quality that is sometimes associated with our perceptions of the eternal and the infinite through history and science. Likewise, it can also be found in great music and art that creates a sense of awe, mental abstraction, or universality. The common factor in all this seems to be the distancing of our minds from our immediate sense and ego perceptions of the here and now. In other words, spirituality is the psychological opposite of the ego and the sensations that sustain it.

Any artist who softens the sensory impact of his work and introduces comparatively timeless themes, like mountains, the sea, and the cycle of the seasons into his work, as Higashiyama does, runs the risk of being thought ‘spiritual.’ But Higashiyama’s art also operates for many viewers on a more purely personal and sensory level, that is the antithesis of spirituality.

The clue to this is the deserted nature of the works and the cropping of many of the images to amplify the rich sensory impact of nature. The golden crispness of the leaves in “Passing Autumn” (1990), the distant hum of a waterfall in “Evening Silence” (1974), and the seductive glow of the full moon rising over the treetops in “Cherry Blossoms in the Evening” (1982) have a strong sensual and epicurean quality.

The way in which the elements of nature are singled out for sensory consumption is remarkably similar to how a good haiku works. What Higashiyama seems to be offering the viewer is a selfish, sensually indulgent ‘virtual moment’ to him or herself; enjoying an aspect of Nature, without anyone else cluttering up the scenario; a chance to switch off the other people we are all connected to and tune into ourselves.

|

| Vibrant Green (1982) |

Seen in this way, it is easy to understand the immense popularity of Higashiyama’s paintings in Japan. But they are loved not because of their ‘spirituality,’ but because they give us a quiet chance to bask in our own egos.

C.B.Liddell

Japan Times

1st May, 2008

Post A Comment

No comments :